You don’t have to specialize in longform to borrow techniques of the genre, and if you’re going to borrow, you might as well borrow from a master, The New Yorker staff writer Lawrence Wright.

Longform is the au courant name for feature stories, specifically longer features and narrative nonfiction that borrows heavily from fiction writing and can run 5,000 words, 10,000 words or longer.

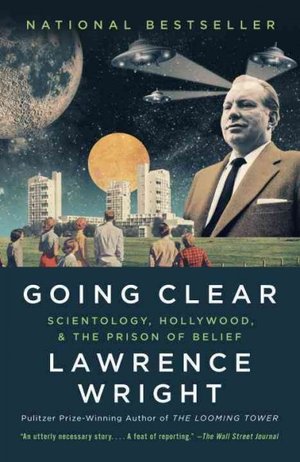

Wright wrote Going Clear, an exquisitely detailed biography of L. Ron Hubband and the origins and modern day workings of Scientology, which followers call a religion and former members and governments have called a cult, a fraud, and worse. The book was a national bestseller and finalist for the 2013 National Book Award for nonfiction.

Wright is a long-time practitioner of long-form journalism. In addition to his work for The New Yorker, he won the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for non-fiction for The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11.

I read Going Clear in one manic 24-hour period on vacation last week – sort of like reading the longest magazine article ever. Consuming it in one sitting was a opportunity to dissect how he put the book together, and what journalists can learn – and take – from the methods he used.

Longform story techniques

Here are some longform techniques Wright uses that any reporter can benefit from:

Talk to a lot of people. Wright did 200 interviews for the book, according to Going Clear promotional blurbs. He talked to past Scientology members, (some) current representatives of the organization, L. Ron Hubbard’s family and friends, and experts in science fiction, psychology, religion and other areas relevant to the subject. Doing such extensive interviewing helps flesh out a story, but also provides for exacting detail and colorful anecdotes — the kinds of things that can make a 1,000-word article or a 462-page book easy reading.

Use a variety of source materials. In addition to interviews, Wright based the book on information culled from public documents such as lawsuits and divorce proceedings, newspaper and magazine articles, books by and about Hubbard, transcripts of Hubbard’s speeches and lectures, Scientology literature, and old photographs. When you’re reporting a story, think about what types of materials might be out there that could support what you learn from interviews.

Reference other publications that have covered the same thing. Going Clear isn’t the first lengthy non-fiction work to delve into the inner working of Scientology. Rather than pretend they don’t exist, Wright uses them to flesh out details of his own story – and footnotes his work so readers can see exactly where he got it. Going Clear has 55 pages of citations.

Fact check everything.Wright’s inspiration for the book was a two-part profile of Paul Haggis, the Hollywood writer and one-time Scientology supporter, that ran in The New Yorker in 2011. Wright and members of the magazine’s fact checking department spent six months confirming the information contained in that piece. Spending that much time on fact checking is an extreme example. But it’s a reminder that even when you’re filing a 500-word blog post, it’s important to fact check your work — especially at a time when many newspapers, magazines and online publishers operate with a barebones copy desk, if they have one at all. Different writers have different preferences for sharing their fact-checked work. I write in Word, and use Word’s comment bubbles to share links or notes an editor or fact checker could use to verify the material. Another freelancer I know submits two versions of stories, one annnotated with information for fact-checking purposes, and a clean copy for her editor. For some publications I write for, I also submit a source list at the end of an article, to make it easier for a copy editor or fact checker to contact sources.

Offer sources with differing opinions the chance to be heard. Good reporting tells both sides of the story. Wright uses his research to tell his version of Hubbard’s life and the birth of Scientology. While he was writing about Haggis for The New Yorker, he and his editor invited Scientology representatives to come to the magazine’s office to go over material they had concerns about, including 971 questions from New Yorker fact checkers (yes, 971! see Going Clear, pg. 424). Wright spends a good deal of one chapter sharing the group’s answers and positions on certain subjects that were opposed to the conclusions he came to, and refutes a number of those positions with conclusions drawn from his own research. The Church of Scientology International continues to maintain that Going Clear contains numerous errors, which the organization has enumerated on a special website, which you can see here.

Take your time. The news business places a lot of emphasis on being first with a story. While there’s definitely a market for that, there’s also a market for a tale that goes into the nuances of a subject, which takes time to report, and time to tell. Think slow cooker pulled pork sandwich v. fast food burger – which would you rather consume? Wright’s New Yorker article on Haggis appeared in February 2011, which means he worked at least another year on Going Clear before it was published. Another longform piece I’ve dissected here before is Bryan Appleyard’s UK Times profile of Steve Jobs written in 2009, two years before the Apple CEO died of pancreatic cancer. Appleyard’s story appeared months after the Wall Street Journal was first to report on Jobs’ liver transplant, an event that Apple never publicly discussed despite persistent rumors of Jobs’ continuing poor health. Appleyard and the Times opted to take the time to prepare an in-depth profile with the kind of quotes that make you think, how did he get people to say that on the record?

My fav longform articles and books

If you’re interested in learning more about longform techniques, you can take workshops, and read pieces on sites Atavist. Or you can read longer works of narrative nonfiction. Here are some I recommend:

Longreads Best of 2013 – The longforum site’s picks for best narrative nonfiction of last year.

The Best Magazine Articles Ever – Kevin Kelly’s curated list of some of the best things to appear in the pages of Esquire, The New Yorker, Wired, Rolling Stone, and more. If you’re only going to read a few, I suggest Gay Talese’s “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” David Foster Wallace’s “Shipping Out” (retitled “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again” in his 1997 essay book of the same name), Tom Junod’s “The Falling Man” and Jon Krakauer’s “Into Thin Air.”

Seabiscuit and Unbroken – The subjects of Laura Hillenbrand’s books couldn’t be more different – a prize-winning horse and a war hero – but both feature the same meticulous research.

Barbarians at the Gate – An artful depiction of the merger and acquisitions madness that was Wall Street in the late 1980s as exemplified by the leveraged buyout of RJR Nabisco, written by financial journalists Bryan Burrough and John Helyar.

The Devil’s Candy – Former Wall Street Journal movie critic Julie Salamon’s searing takedown of Brian De Palma’s film adaptation of Tom Wolfe’s best-selling book The Bonfire of the Vanities. The movie was a flop, and Salamon had complete behind-the-scenes access to the cast and crew to show why.

The Power Broker – Robert Caro’s profile of New York City master builder Robert Moses is perhaps one of the best examples of long-form nonfiction narrative of the 20th century. I read Power Broker as a journalism school grad student. It was assigned reading in a class on reporting on civics and government, but it could serve equally well as an example of the tenacity and determination it can take to pull off such a massive work.

Other good longform reads: Friday Night Lights; Homicide: Life on the Streets; Moneyball.